|

In 1806 Ephraim Small was 20 when he decided to try his luck back on the coast, having had enough of farming. In 1803 his father, Ephraim Sr. had traded a wagonload of seasoned curly maple for some property in the town of Bath and built a small house there on the banks of the Kennebec. Young Ephraim moved in and began looking for work.

The job Ephraim found was in the saw-mill owned by William King. He came to King’s personal attention when he interrupted a lumber stealing operation at the King mill. King learned that Ephraim was good with figures so he transferred him from the mill to his business office where Ephraim helped keep track of the growing King enterprises.

In his capacity as bookkeeper Ephraim had occasions to visit the King household. There he saw an icebox where food was kept cool year round. The ice was kept in an icehouse on the property, banked with sawdust from the mill so that it would not melt. Ephraim immediately thought of marketing ice to the public from a large central icehouse rather than having ice only available to people who could afford to have their own icehouse.

He studied the construction of the icebox and concluded that a good carpenter could turn them out about one per day if the parts were pre-cut to fit. His idea was to mass produce the iceboxes and give them to homeowners for as long as they subscribed to his ice service.

When William King, the sharpest businessman in Maine declined to invest in the ice business, Ephraim should have guessed that there was a problem but he was convinced that it would be his everlasting fortune. He borrowed heavily elsewhere, built the icehouse, stocked it with ice in the winter of 1806-1807 and sold enough ice during the summer that it took him over two years to go broke. It remained for Frederick Tudor of Boston, who also went broke on his first attempt, to market New England ice around the world to places where it was hot all the time.

William King, who was fond of Ephraim, made deals with his creditors to keep him out of jail but Ephraim’s name was tainted by the scandal. So it was, that when he asked Isaac Higgins for his daughter Anna’s hand in marriage, Mr. Higgins said, “Of course not”.

Anna however was having none of that. She loved Ephraim in spite of his troubles so she eloped to Bath to marry him there in February 1809. In September they had a son Benjamin who died shortly after birth. By Christmas of 1809 all was forgiven and Ephraim, with Anna, moved back to his father’s farm.

In the spring of 1810 Ephraim was exploring the land east of his father’s farm with the idea of establishing a farm of his own. The property was not well suited to farming, being steep and rocky but it might be all Ephraim and Anna could afford.

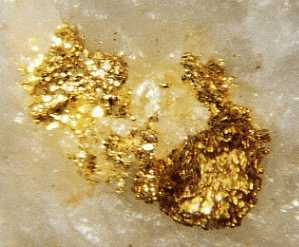

He was sitting on a rock outcropping pondering his financial problems and poking at the ground with a stick when he broke through the thin topsoil into a pocket of sand and gravel. Intrigued by the regularity of the pebbles imbedded in the sand, he scooped out a handful to look more closely at them. There among the grains of sand were a few bright yellow flakes.

Ephraim had never seen gold in the wild, as it were, but had seen gold coins and knew that the metal was mined from the ground. He hurried home with his sample and spoke only to the two most discrete people he knew, Anna and his father.

“Gold and greed go hand in hand.” said Ephraim Sr. They decided to limit their mining operations to just that needed to finance the proper farm that Ephraim and Anna needed. Ephraim Sr. purchased a few acres on the hillside, surrounding the discovery and he an Ephraim dug a strategically placed cellar for their “mountain cottage”. A structure they actually built to disguise the gold mine. They found that the gold mostly accumulated in depressions in the bed rock.

Maine Gold Deposit

To avoid questions about the source of the gold, Ephraim became a prospector and traveled about fifty miles northwest into the hills of Oxford County a couple times a month. He returned from these trips to sell his ounce or less of gold at one of the towns along the way or in the vicinity of home, rotating among the dealers so as not to arouse any curiosity. In this way, without attracting much attention, he began to accumulate the capital for a farm.

On one of the “prospecting trips” Ephraim was tramping through the hills when he came across a blown down tree spanning a stream and walked along the trunk from leaf to root. After reaching the bank he looked back at the upturned roots which had torn up a mass of earth exposing the underlying soil. A glint of reflected sunlight in that soil caught his attention.

Ephraim took a stick and poked at the soil to turn up a pink and pale green crystal with three faces. Digging through the rest of the exposed soil he found another clump of dark blue crystals embedded in rock. He pocketed the unusual stones and continued on his walk.

Ephraim came out of the woods to the meadow where he had tethered his horse and mounted up to ride back to Lewiston on the Androscoggin River. There he took a room for the night and in the morning took the half ounce of gold, brought from home, to the saw mill operated by Michael Little. The Little mill had a small office in the back where gold could be sold. It was one of several places Ephraim had found to unload his gold.

“Hello there Ephraim,” said the mill manager, Stewart Hibbs, who was handling Ephraim’s gold. “I see you are still trying to scrape up wages up in Oxford County.”

“Yep. Found some pretty rocks yesterday when I was trying to add to my stash.”

Ephraim pulled the stones from his pocket and displayed them.

“Huh. Looks like some kind of gemstones,” said Stewart. “I don’t know anything about them. You ought to take them over to Harold Day in Gardiner. He is a jeweler and deals in gems and I know he will be honest with you.”

So that is what Ephraim did that afternoon.

“Mr. Day?” Ephraim said when he located the jewelry store on the river road in Gardiner.

“Yes sir. What can I do for you?”

“Stewart Hibbs over in Lewiston suggested I look you up. My name is Ephraim Small, from Bowdoin.”

“Pleased to meet you. I believe I met your father, of that name, back in ’97 or maybe ’98.”

“I found some interesting rocks under the roots of a blown down pine and Stewart said you might know something about them.”

Ephraim laid the stones on the counter and Mr. Day picked them up one at a time and examined them closely.

“I believe that is blue schorl in that quartz. Really good examples of it. The pink and green may be the same sort of stone but I haven't seen one like that. Where did it come from?”

“Oxford county.”

“Oxford is a big county.”

“Yes sir. It surely is.”

Mr. Day laughed.

“Look,” he said. “These stones are worth quite a lot of money. I need a day or two to separate the entrapped stones from the rocks and to measure and weigh the gems. Let me give you a receipt for them and come back Thursday. Then maybe we can talk business.”

So Ephraim and Mr. Day met again Thursday afternoon.

“Here are your pieces of schorl. If you want to sell them to me I will pay you twenty dollars silver for the raw gems.”

“What would it take to make a necklace out of that largest piece there?”

“With that one I would make it a rectangular cut with a flat face and beveled edges. It could be quite nice. Probably mount it in gold alloy with a gold chain… or could do it in silver.”

“Would you do that for me in gold for all those blue-black stones?”

“That would take quite a bit of gold. I could do it in silver that way.”

“I have scraped together a bit of gold over the years. If I were to provide the gold how much of it would you need?”

“If you could come up with a quarter ounce I would make you a really nice necklace for the other stones.”

So in due course Anna had a beautiful necklace of the gem we today call watermellon tourmaline and Ephraim had his farm of about 100 acres east of the hills in Richmond on White Road about 2 miles from the Kennebec River.

Ephraim Sr. made the transaction to further hide Ephraim’s sudden prosperity. The farm became known as the Patriot Small’s property, referring to Ephraim Sr. The only gold taken from the mine above that required for the farm was enough to repay William King for his help in bailing Ephraim out of the ice business. When the mine was shutdown, much of the rather deep and wide cellar of the mountain cottage was quietly filled in. No one but Anna and the two Ephraims ever knew the whole story.

During the war of 1812, in September, 1814, the British seized all the district of Maine east of the Penobscot River. Massachusetts took no action to repel the British so President Madison nationalized the Maine militia and placed William King in command as major general. Ephraim signed up as soon as the news reached Richmond. His father, Ephraim Sr. the veteran of Arnold’s campaigns in the war for independence, also joined up at the age of 53.

The militia marched around and drilled with wooden weapons but the United States had no funds to provide arms or equipment to the militiamen so when peace came in February of 1815, the role the militia played in the conflict was open to interpretation. Ephraim Sr. said that the British surrendered because the population had risen up against their occupation of the eastern half of the state. Ephraim Jr. said it was the black flies that drove the British from Eastern Maine. He himself had not seen a single British soldier anywhere near Richmond, and he was pretty sure that none of them had seen him.

Ephraim Jr. and Anna had 12 children:

Benjamin Small, 9/22/1809, died young

Benjamin R Small 11/22/1810, Bowdoin, ME

Nathaniel Small 2/28/1812, Bowdoin, ME

Deborah Small 8/21/1814, Richmond, ME

Hezakiah Small 12/14/1815, Richmond, ME

Ann Small 12/15/1816, Richmond, ME

Ephraim Small, 6/27/1819, Richmond, ME

Richard Small 10/1/1821, Richmond, ME

Elizabeth Small, 2/14/1824, Richmond, ME

Dorcas M. Small, 3/19/1826, Richmond, ME

James M. Small 3/26/1828, Richmond, ME

Gilbert B. Small, 3/3/1830, Richmond, ME

In 1853 Ephraim sold the farm to his youngest son Gilbert, who had already become a successful farmer at the age of 23. The price was $500, which was more than the market value, and the deed stipulated that Ephraim and Anna would have the use of the property as long as either lived. Young Gilbert made sure the old folks were taken care of.

Ephraim died in December, 1862 and Anna in November of 1869.

|